What is El Niño?

Peruvian fishermen noticed it over a century ago. Around Christmas, the normally productive waters off their coast would sometimes turn warm and the fish would vanish. They named the phenomenon El Niño, “the little boy,” after the Christ child. What they were observing from their boats was one end of a system that spans the entire Pacific basin, a cycle called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

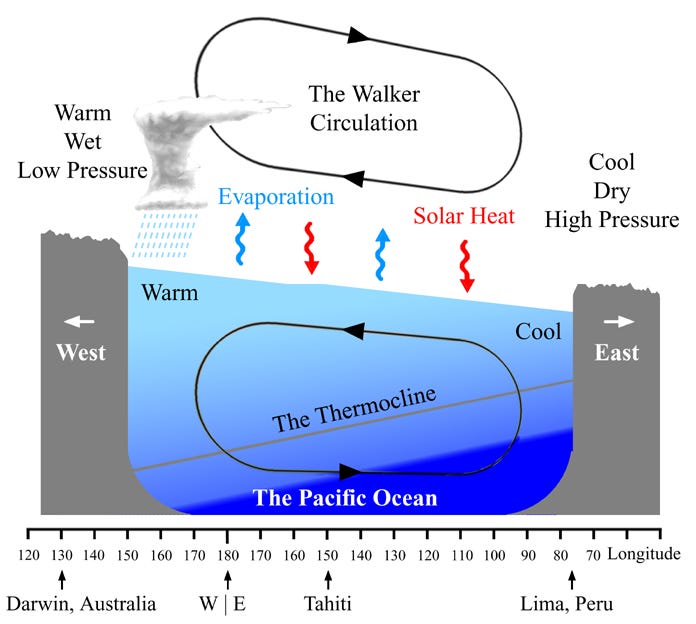

Under normal conditions, trade winds blow westward across the tropical Pacific. These winds push warm surface water toward Indonesia, raising sea level in the western Pacific relative to the east. The sea surface near Indonesia sits about half a meter higher than near South America, and the temperature difference is stark, with waters near Peru capable of running 6-8°C cooler than those in the western Pacific. This gradient exists because the trade winds drive coastal upwelling along South America, pulling cold, deep water to the surface.

The temperature difference then reinforces itself. Warm water in the west heats the air above it, causing it to rise and generating heavy rainfall over Indonesia and northern Australia. That rising air has to go somewhere, so it flows eastward in the upper atmosphere before sinking over the cooler eastern Pacific. The sinking air flows back westward at the surface, completing the loop and strengthening the trade winds that started the whole pattern. This atmospheric circulation is called the Walker circulation, and the ocean and atmosphere are locked in a feedback loop where each component reinforces the other.

El Niño happens when this system weakens. If something causes the trade winds to slacken, the warm water held in the western Pacific starts to slosh eastward. As the eastern Pacific warms, the temperature difference across the basin shrinks. A smaller temperature gradient means weaker Walker circulation, which means weaker trade winds, which lets more warm water flow east. Once it gets going, the warming amplifies the conditions that caused the warming in the first place.

La Niña is the opposite. Trade winds strengthen beyond their normal state, pushing even more warm water westward and enhancing the upwelling of cold water in the east. The temperature gradient steepens, reinforcing stronger winds. Where El Niño brings warming to the eastern Pacific, La Niña brings cooling.

If this feedback only worked in one direction, the system would get stuck. El Niño would keep amplifying until it ran out of warm water, or La Niña would lock in permanently. What allows the system to oscillate is the thermocline - the layer where ocean temperature drops rapidly with depth, separating warm surface waters from the cold deep ocean. When trade winds change, they trigger waves that travel along this density boundary beneath the surface. These aren’t the surface waves we surf. Kelvin waves propagate eastward along the equator, adjusting the thermocline depth as they go. The process takes weeks to months, introducing a delay into the system. By the time these subsurface signals cross the Pacific and adjust the thermocline in the east, the delay is enough to set up a reversal.

The whole cycle takes roughly two to seven years, though the timing is irregular. Some decades see multiple El Niño events, others see few. The intensity varies too. The 1997-1998 and 2015-2016 events were among the strongest on record, while others barely register. NOAA officially declares El Niño when sea surface temperatures in the central-eastern Pacific exceed 0.5°C above normal and hold there for several months.

The Peruvian fishermen had the timing right - El Niño events typically peak around December. But the cycle’s irregularity makes it notoriously difficult to predict, a problem that has occupied oceanographers for decades. And for those of us who surf, the state of the tropical Pacific has consequences that reach far beyond anchovy populations. More on both of those next.

Further Reading: