How is wave energy measured?

Physics is all about energy. Not the “vibe” kind, but a measurable quantity of something's ability to do work. It takes various forms - from roller coasters poised at their peak to waves rolling across the Pacific. While most of us think about wave energy in terms of how much water is about to rail us into the sand, we can get more precise than that.

The most direct way to measure wave energy would be adding up the energy of every water molecule in the wave - both their motion (kinetic) and height above sea level (potential). One small problem: a single drop of water contains roughly 1.5 sextillion molecules. That’s the horrific equivalent of over 3 billion billion of Elon Musk’s net worth. Free speech would be oh so free. Keeping track of any amount of individual molecules on this scale is currently impossible with the best computers.

Instead, we use statistics. By assuming the ocean is homogeneous (one handful of water is identical to the next), we can work with averages. The energy depends on water density, which varies with temperature and how much salt and other materials are dissolved in it.

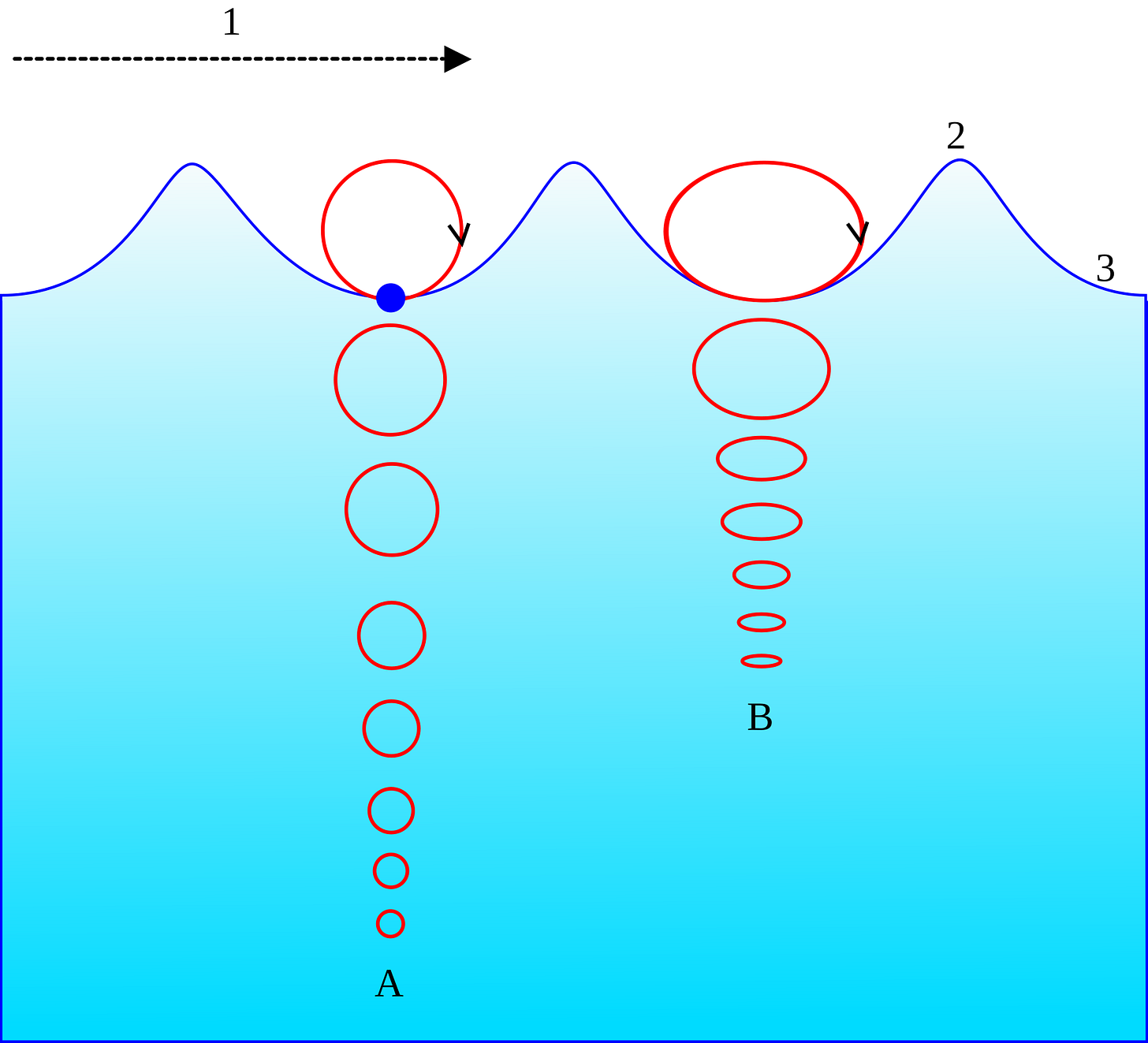

Deep water waves behave differently than shallow ones. In deep water, particles move in nearly perfect circles, returning to where they started. This symmetry means kinetic and potential energy are equal. Both depend on three factors: water density, gravitational acceleration, and wave height squared. Denser water means more energy, waves on Jupiter pack more punch due to stronger gravity, and bigger waves carry exponentially more energy.

Shallow water waves occur when wavelength approaches or exceeds water depth. A 12-second period swell, with its 100+ foot wavelength, acts like a shallow water wave in 20 feet of water. Meanwhile, a 2-inch wind ripple behaves like a deep water wave in the same spot.

The shallow water energy equation gets more complex. Bottom friction saps energy from waves, while refraction redistributes it along the wavefront. The energy still depends on gravity, density, and height, but now wavelength and water depth play crucial roles. In very shallow water (wavelength roughly 20+ times the depth), the wave's energy becomes more concentrated as the wave height increases due to shoaling, though the total energy remains constant unless dissipated by friction. Below is the energy density for deep water waves:

Here, rho (the greek letter that looks like a p) is the density, g is the gravitational acceleration, H is the wave height, and lambda (the upside-down y) is the wavelength.

In the linear case, deep water waves are smooth, with peaks as wide as troughs. As waves move into shallower water, they transform - peaks become narrower and taller while keeping the same total water volume. While this doesn't change the total energy, it packs that energy into a smaller area. For surfers, this means more power concentrated in the impact zone as the wave starts to break.

The shallow water equation, which is more nuanced than a 2-minute read allows me to derive here, tells us how this concentration of energy happens, with water depth playing a key role. When the water depth is much greater than the wavelength (deep water case), the equation simplifies back to our deep water formula. But physics sets some natural limits - you can't have infinitely tall waves in ankle-deep water, even if the math suggests it's possible.

Most wave data comes from offshore buoys and needs to be extrapolated to the beach. Since energy depends on wave height squared, small measurement errors can mean big surprises between forecast and reality. Bottom friction and refraction are particularly hard to account for in forecasts. And since the energy concentrates in shallower water, that washing machine you're paddling through might have more juice than predicted.

Further Reading:

Falk Feddersen’s Notes (basically the syllabus for one of his graduate classes)