What's inside your surfboard?

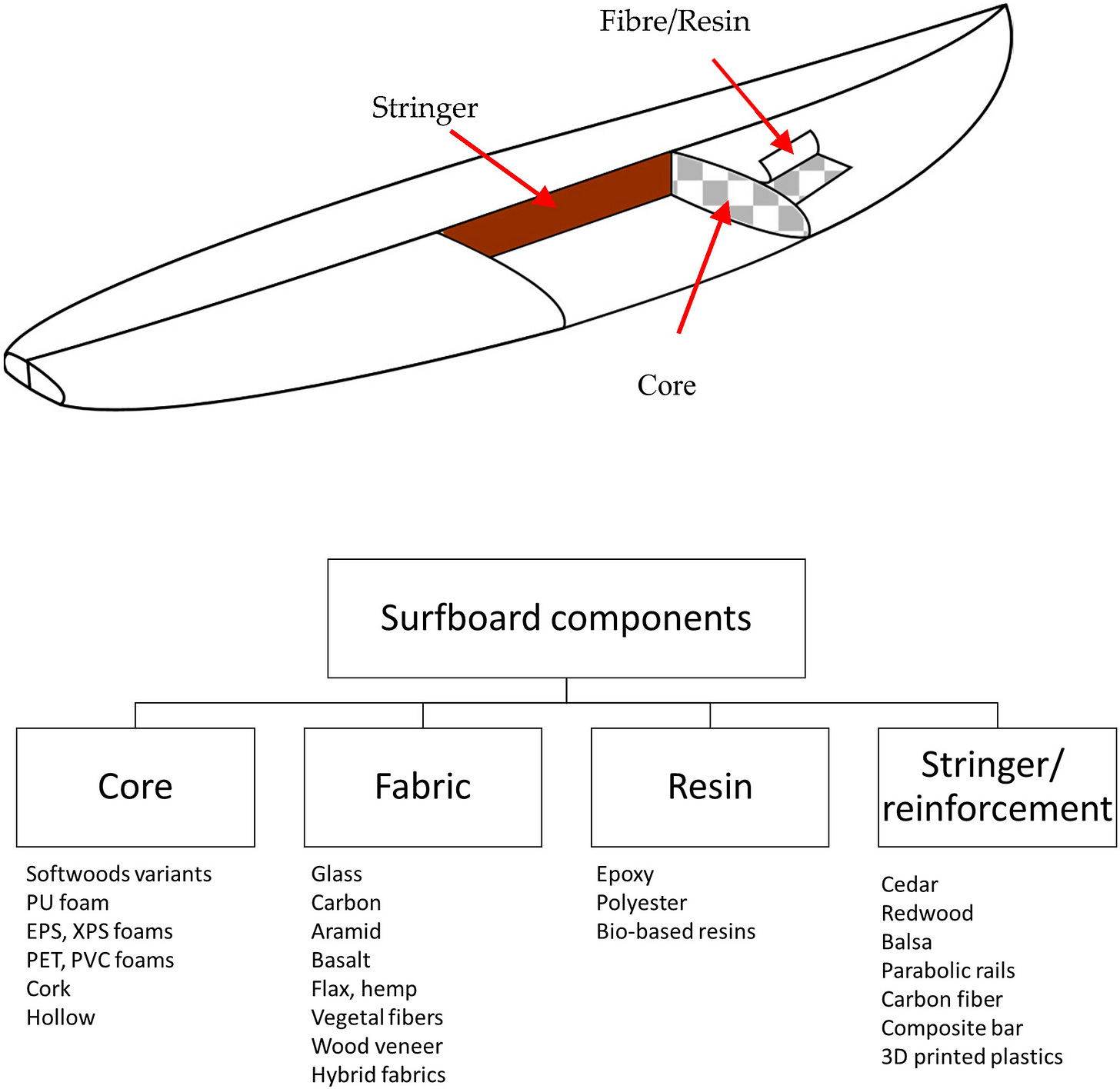

Crack a board in half and you’ll find roughly the same thing whether it costs $100 or $1,200: foam wrapped in fiberglass. This sandwich structure has been the standard since the late 1950s. The foam core distributes loads and keeps weight down while the outer skin of fiber and resin handles bending and compression. Simple in concept and used in tons of boats and watercraft, but with many variations.

Polyurethane foam is the surfing OG. Its density sits between 25 and 40 kg/m³, with shapers selecting blanks based on the weight and durability they’re after. Polyol reacts with isocyanate in a thermosetting process that can’t be reversed. So, once cured, PU foam is PU foam forever, which matters when you consider that 25-30% of each blank ends up as shaping dust headed for a landfill. Clark Foam supplied most of California’s shapers until 2005, when the operation shut down overnight and left the industry hanging.

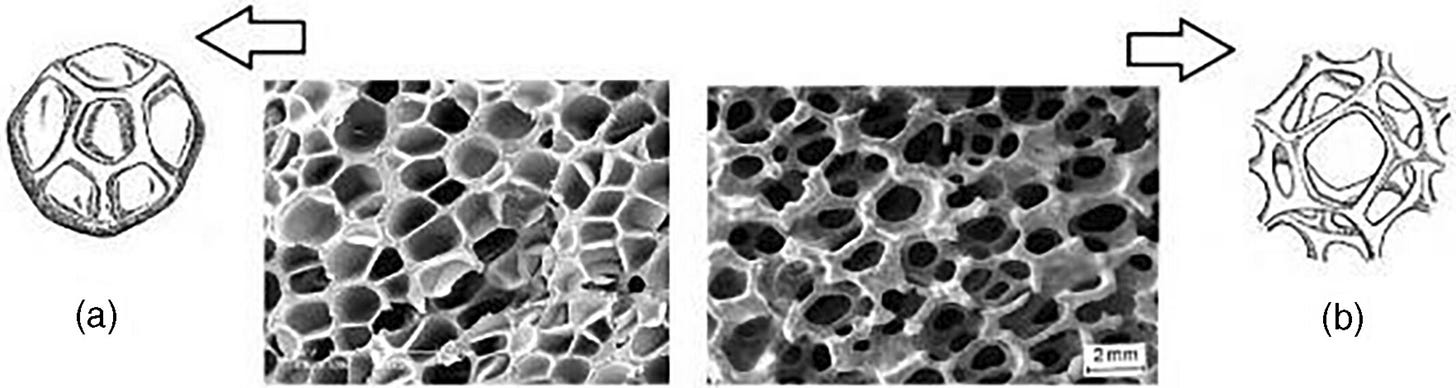

Expanded polystyrene started to fill the void. EPS runs lighter than PU at equivalent strength, with densities from 14 to 40 kg/m³ and a closed-cell structure that resists water absorption. The shaping scraps can be recycled since the material isn’t cross-linked like PU. But EPS has compatibility issues. Pour polyester resin on it and the foam dissolves, so boards must be glassed with epoxy, which demands precise mixing and costs more. Heat is also a weakness for EPS. If you leave an EPS board in a hot car, the foam can warp permanently.

Running nose to tail through most boards is the stringer, usually a strip of cedar, redwood, or balsa. It adds longitudinal stiffness and helps maintain rocker as the board ages. Carbon fiber and cork have entered the stringer market, each with different flex characteristics. Some EPS boards ditch the stringer entirely since the foam can be stiffer than PU on its own, though removing it changes how the board responds under your feet.

E-glass fiber dominates the outer skin because it’s cheap and available. S-glass costs more but delivers roughly 30% greater strength and 15% higher stiffness: one ply can match two layers of E-glass. Carbon fiber tops both in strength-to-weight, though manufacturing complexity pushes the price up substantially. The fibers do the structural work; the resin bonds everything together and seals the foam from water. Polyester resin cures fast and costs less but tends toward brittleness. Epoxy is stronger, more flexible, better at absorbing impacts. Since EPS requires epoxy anyway, plenty of shapers have switched over entirely regardless of what foam they’re using.

Buried under the glass are the parts you bolt things to. Fin boxes - whether FCS, Futures, or glass-ons - are composite or plastic inserts that need to bond with both foam and skin without creating stress points. Leash plugs are similar: a small cylinder glassed into the tail that takes repeated yanking every time you wipe out. These components don’t get much attention until one strips out or delaminates. But that’s a great opportunity to double check if you’re working with PU or EPS before grabbing a poly resin repair kit.

Further Reading: