Do electric shark deterrents work?

Tiger sharks, those apex predators with jaws powerful enough to bite through turtle shells, turned out to be the picky eaters of the group.

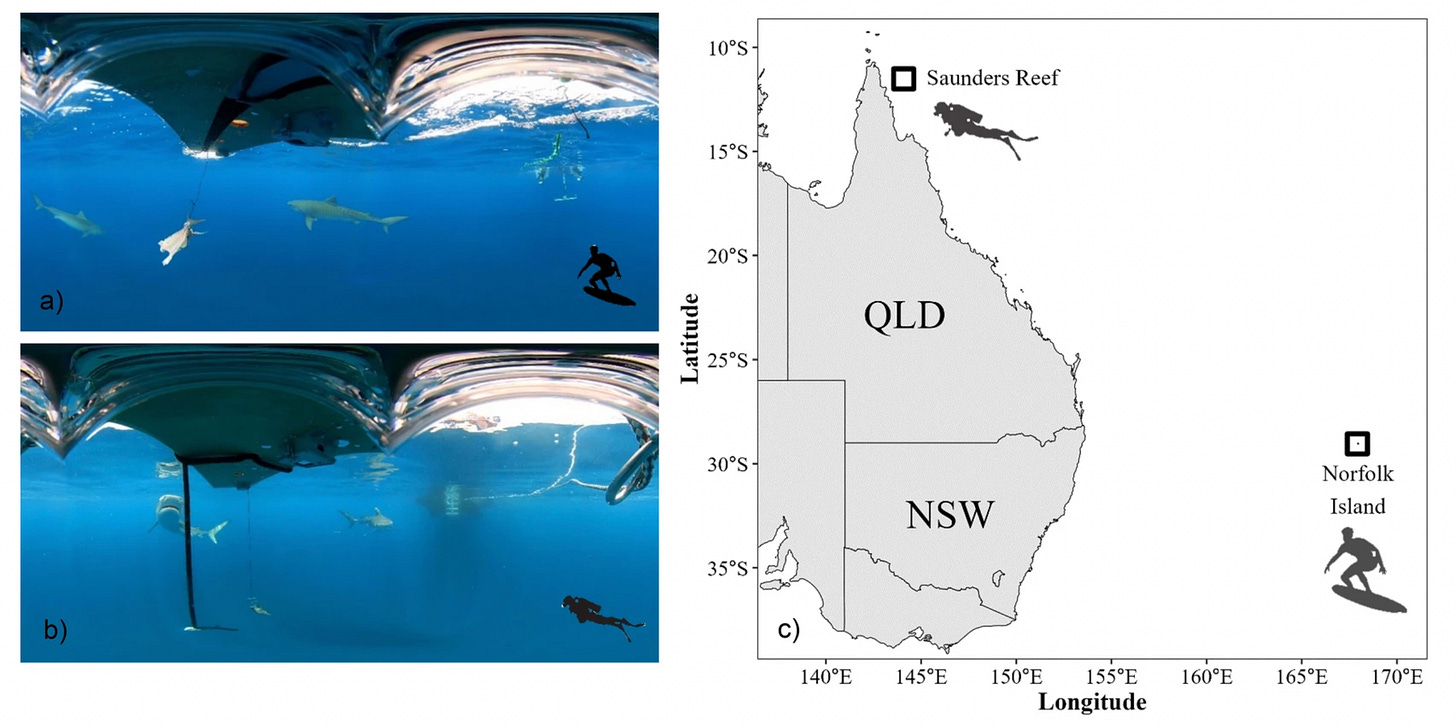

Researchers at Flinders University hauled their gear to Norfolk Island, a volcanic speck 1,400 kilometers east of Australia where the Pacific drops to abyssal depths just offshore. The isolation means resident tiger sharks haven’t developed the same aggressive feeding behaviors seen around heavily fished continental shelves. Perfect for testing whether electronic shark deterrents actually work when sharks want to bite, not just when they’re casually swimming by.

The team needed conditions where sharks desperately wanted to feed. They dangled fresh fish half a meter below surfboard replicas, chummed the water until it reeked of blood and fish guts, and let multiple sharks compete for a single piece of bait. Previous deterrent studies tested whether devices work during normal encounters. This study asked whether they work when sharks are actively trying to eat

.

Ocean Guardian’s Freedom+Surf electric deterrent (unfortunately no failed to stop all bites, but it consistently made sharks hesitate. Tiger sharks bit the bait 67% of the time with the device off, dropping to 22% when electricity pulsed through pads mounted along the board’s bottom. Bull and white sharks showed similar reductions, cutting bite rates roughly in half across all three species responsible for most serious attacks worldwide.

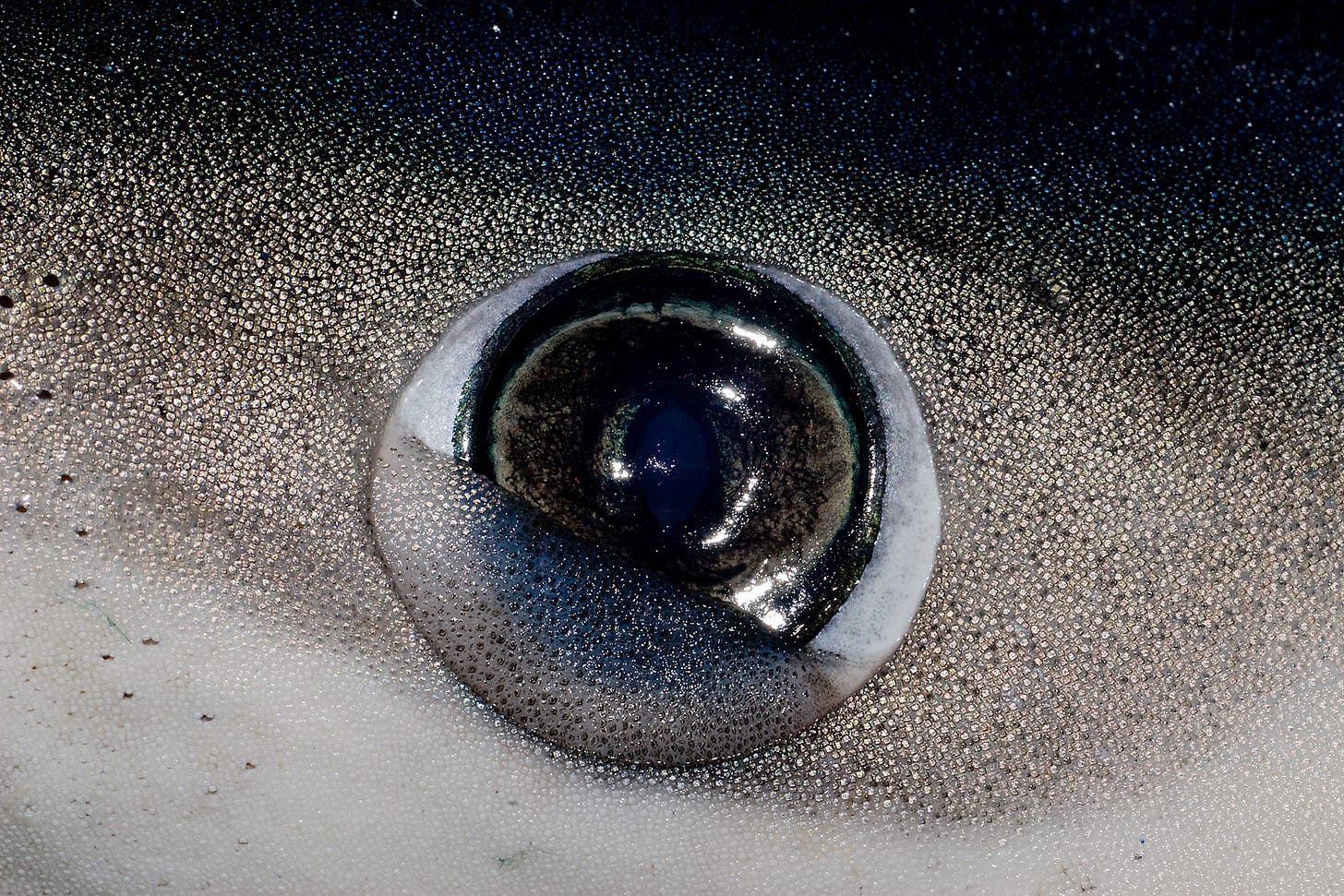

Bull sharks provided the most dramatic reactions. Their nictitating membranes - protective eyelids that normally flicker briefly around prey - started closing constantly when the deterrent activated, like someone was jabbing them with a cattle prod. The reason lies in their electroreceptor system. Bull sharks pack 1,852 of these specialized pores around their heads versus 812 for white sharks and 798 for tigers. Sharks use these receptors to detect the electrical fields generated by all living things, particularly the muscle contractions of struggling fish. More receptors means more sensitivity and hunting success in turbid waters, but also more vulnerability to electrical interference.

The contrast with white sharks was stark. White sharks barely reacted to the deterrent pulses. They lack nictitating membranes entirely and simply roll their eyes back when attacking, trusting their momentum to carry them through. Tiger sharks fell between the extremes, showing moderate discomfort but nothing approaching the bull sharks’ obvious distress.

Norfolk Island’s isolation created ideal testing conditions but also highlighted the study’s limitations. These sharks hadn’t learned to associate boats with easy meals, unlike their continental counterparts who follow fishing vessels. The extreme feeding scenario - multiple sharks fighting over fresh bait in chummed water - doesn’t reflect typical surf conditions where sharks investigate surfers out of curiosity rather than hunger.

Individual sharks responded differently regardless of species. Some consistently avoided the electrodes while others pushed through the discomfort to reach the bait. The deterrent created hesitation rather than avoidance, forcing sharks to reconsider before committing to a bite. Whether those extra seconds provide meaningful protection depends on how quickly you can spot trouble and clear the area.

Shark deterrent research has struggled with the ethics and logistics of testing devices under realistic attack conditions. Most studies observe sharks swimming near inactive deterrents, then infer effectiveness from behavioral changes. The Norfolk Island study represents one of the few attempts to measure deterrent performance when sharks actively want to bite something, using a setup designed to maximize aggression rather than minimize it.

The Freedom+Surf reduced attack rates in all three species, but didn’t eliminate them. For surfers entering waters where these species hunt, that reduction may represent the difference between encountering a curious shark and one that’s already decided to investigate with its teeth.

Ocean Guardian closed up shop, meaning the specific device tested in this study is no longer available. However, the company has been purchased and the device will hopefully come back on the market. While the research validates the underlying technology, anyone considering electric deterrents would need to evaluate currently available alternatives against this scientific benchmark. The study’s value lies not just in proving one product worked, but in demonstrating that electric deterrents can meaningfully reduce shark bite risk when the engineering gets the details right.

Not perfect protection, but potentially enough time to become something other than the most interesting thing in the water.

Further Reading:

Very relevant for me just now. There was a fatality where I used to live a couple of weeks ago. Not a friend but someone I knew well enough to say g’day to in the water. Yesterday, at an isolated beach near where I now live, there were three of us in the water and a 2m shark came to within about 15m. We came in. We saw that one but they are around frequently along the coast.

The odds are always hugely against an attack, so high that the marginal reduction in the risk provided by these devices just doesn’t seem worth the inconvenience and cost of installing them. It is great that the research is being done but for the forseeable future, the vast majority of us will take the usual precautions and continue to accept the risk.