What's the difference between swells and waves?

We surfers tend to use the terms interchangeably. Like the whole finger and thumb thing, all swells are waves, but not all waves are swells. The distinction comes down to where a wave sits in its life cycle and how far it’s traveled from the storm that made it.

Waves still under active wind generation are called “sea” or “wind waves.” These are the choppy, disorganized conditions during a storm or a windy afternoon session. Multiple wavelengths, periods, and directions stack on top of each other with no discernible pattern. The wind keeps dumping energy into the water, pushing existing peaks higher while new ripples form constantly. There’s no rhythm, just overlapping chaos.

Once waves leave the generating area, they become swell. The storm might be a thousand miles away, but the energy it transferred keeps propagating across the ocean. Without wind input, the waves can’t grow anymore, they can only travel. And as they travel, they organize.

We’re adding dispersion to our list of friends: longer period waves move faster than shorter ones in deep water. A 20-second wave crosses open ocean at roughly 35 mph while a 12-second wave manages about 21 mph. Long-period waves pull ahead, short-period waves lag behind, and what started as a soupy sea separates into distinct swells over subsequent days.

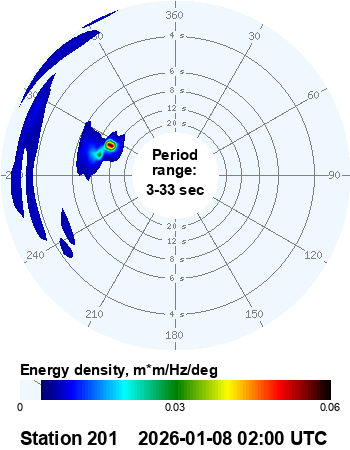

Wind waves typically run periods under 10 seconds and arrive from multiple directions simultaneously. Swells clock in at 10 seconds and longer, often much longer for groundswells from distant storms, with tight directional bands. Pull up buoy spectra during a local wind event and you’ll see broad peaks smeared across frequencies and directions. Clean swell shows narrow spikes. NOAA’s wave models separate “wind wave” and “swell” components, each with their own height, period, and direction. A forecast might show 2-foot wind waves from the northwest combined with a 4-foot swell from the west-southwest. Both contribute to total sea state, but I’m going to bet you’ll like the swell more.

Wind waves lose steam quickly once the wind stops. Their shorter wavelengths dissipate through whitecapping and turbulence. Swells barely decay. Walter Munk tracked swells generated near Antarctica arriving in Alaska two weeks later, having crossed the entire Pacific with enough energy left to register on instruments. Wind chop just can’t handle that sort of distance.

A head-high day of pure groundswell hits very different than head-high wind waves, even if the buoy reads identical wave height. The groundswell arrives in defined sets with consistent faces. The wind waves stack unpredictably with variable steepness and no clear peaks. Period and organization matter as much as size. When someone says “there’s swell in the water,” let’s all hope they mean something fun.

Further Reading: