When do shark attacks occur?

Dawn patrol is special. The offshore winds, the glassy conditions, and according to beach lore, the sharks. Every coastal town has someone who swears they only surf mid-day because that’s when sharks sleep or hunt deep or do whatever it is that keeps them away from the lineup. Beach warning signs frequently tell swimmers to avoid dusk and dawn. The assumption seems universal: low light equals shark danger.

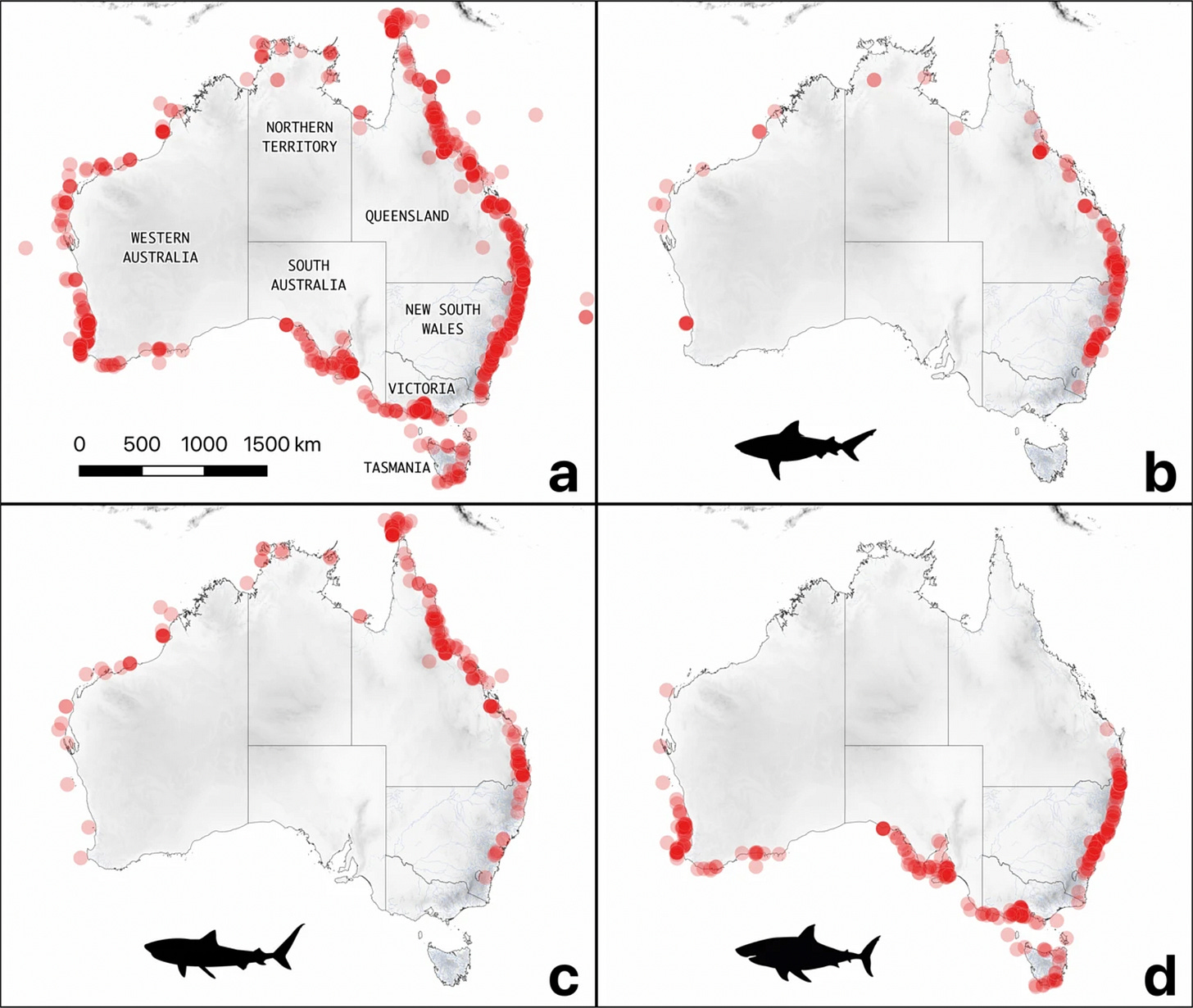

As researchers out of Flinders University have shown, the Australian Shark-Incident Database offers a way to test this. Out of 1,196 total toothy incidents from 1791–2022 in Australia, 540 include recorded times of day. Researchers converted these times into local light conditions rather than just clock hours, accounting for Australia’s sprawling geography and multiple time zones. They categorized each incident as occurring during dawn, day, dusk, or night using the actual position of the sun at that specific location and date.

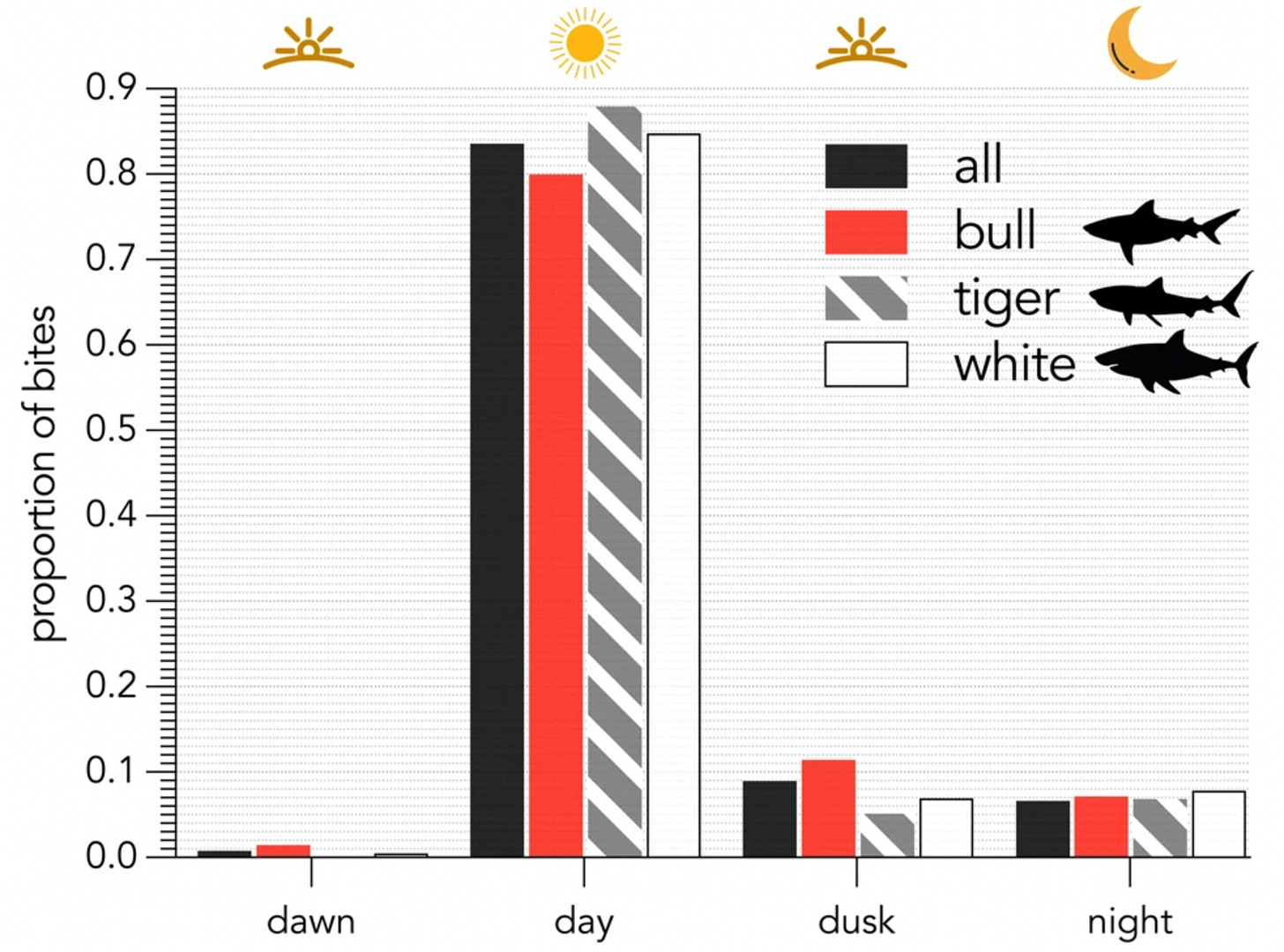

The data demolishes the dawn and dusk narrative, at least on the surface. Over 80 percent of shark incidents happen during full daylight. Dawn accounts for roughly 2 percent of incidents, dusk around 5-10 percent, and night hovering around 5 percent. Those percentages hold relatively consistent across the three species most commonly involved in incidents: white, tiger, and bull sharks.

But this overwhelming daylight dominance probably says more about human behavior than shark behavior. The number of people in the water peaks during afternoon hours when families hit the beach, surfers maximize their lunch breaks, and swimmers seek relief from the heat. Incident rates follow human activity patterns because incidents require two to tango. If nobody swims at 2 AM, there won’t be any 2 AM shark incidents regardless of what sharks are doing.

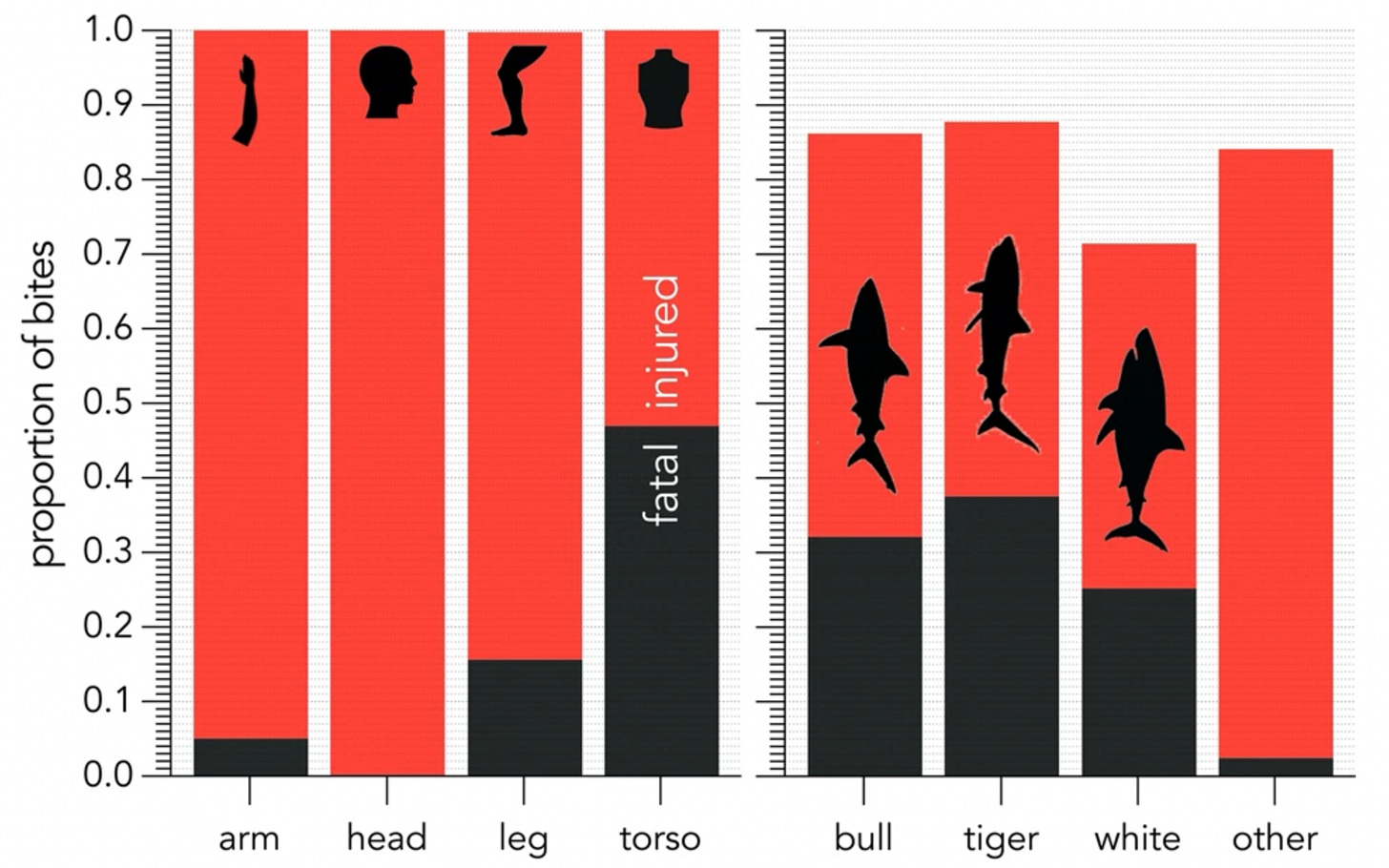

Bull sharks present the one notable deviation. Their dusk incidents occur at nearly double the rate of white sharks and considerably higher than tiger sharks. This could reflect actual feeding behavior, with bull sharks becoming more active as light fades. Or it could simply reflect where and when humans encounter bull sharks. These sharks frequent estuaries, river mouths, and murky coastal waters where people fish at dusk or take evening swims in areas that happen to overlap with bull shark habitat more at that hour.

White sharks account for 217 of the 540 timed incidents, with tiger sharks responsible for 59 and bull sharks for 70. The remaining incidents involve other species or couldn’t be identified to species level. This means white shark patterns heavily influence the overall numbers. All three major species show minimal nighttime activity, but this likely correlates with minimal human nighttime activity in the ocean rather than sharks following any particular schedule.

The database reveals when incidents happen, not when sharks hunt. Controlled studies tracking shark movement and feeding separate from human activity would be needed to determine actual attack risk by time of day. The incident data captures the overlap between human and shark activity, weighted heavily by when humans choose to enter the water. Those dawn patrol warnings might be completely valid from a shark behavior standpoint, but the data can’t confirm it because so few people are in the water at dawn compared to mid-afternoon that incident numbers stay low regardless. However, as surfing becomes more and more popular and dawn patrols and sunset sessions take up a bigger slice of the ocean-use pie, this dataset may shift towards a more low light diet for the sharks.

Further Reading: